In doing this, the evidence will be categorized with respect to deficiency, risk, benefit, and feasibility to increase the effectiveness of public health programs.Įvidence of deficiency is provided by a dietary nutrient intake that is inadequate to meet the requirement estimated to be necessary to avoid a deficient state. This review will also reassess the evidence for iron supplementation and the strength of the evidence that implicates either a low or a high hemoglobin concentration in morbidity and mortality during pregnancy and the perinatal period. The purpose of this review is to look at normal and abnormal hemoglobin values in terms of their causes and consequences. He questions whether efforts to prevent anemia through iron supplementation can put some women at risk by placing their hemoglobin in a higher range that is associated with poor pregnancy outcomes. Specifically, he notes that a high hemoglobin value during pregnancy has been associated with adverse birth outcomes. In this supplement, Rush ( 2) questions the benefit of routine iron supplementation in relation to the evidence of the harm or burden of anemia on reproductive outcomes. Therefore, anemia prevention through iron supplementation may help to improve reproductive outcomes.

Another reason for supplementation is that anemia caused by iron deficiency alone or in combination with other factors, eg, folate deficiency, vitamin A deficiency, and malaria, has been implicated as having several negative effects on maternal and fetal health. Part of the rationale for this practice is the high iron requirement during pregnancy, almost 3 times that required for nonpregnant women of childbearing years, which is difficult to meet from dietary sources ( 1). Iron and folate supplementation during pregnancy is commonly practiced to prevent maternal anemia, which is often caused by iron deficiency.

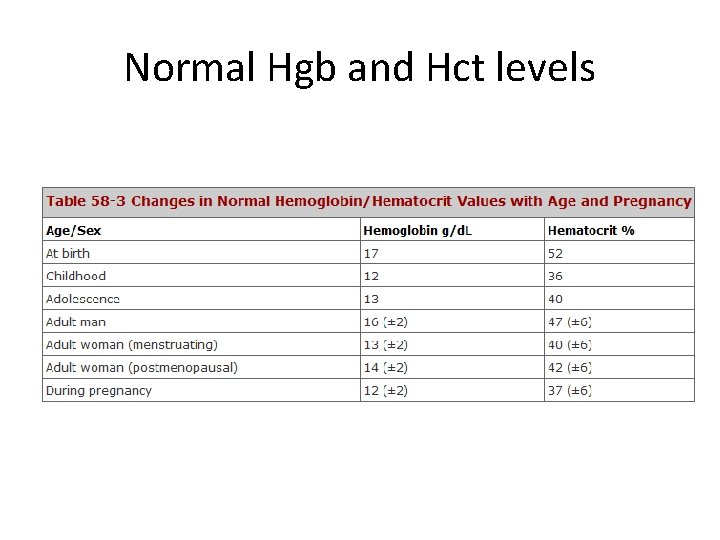

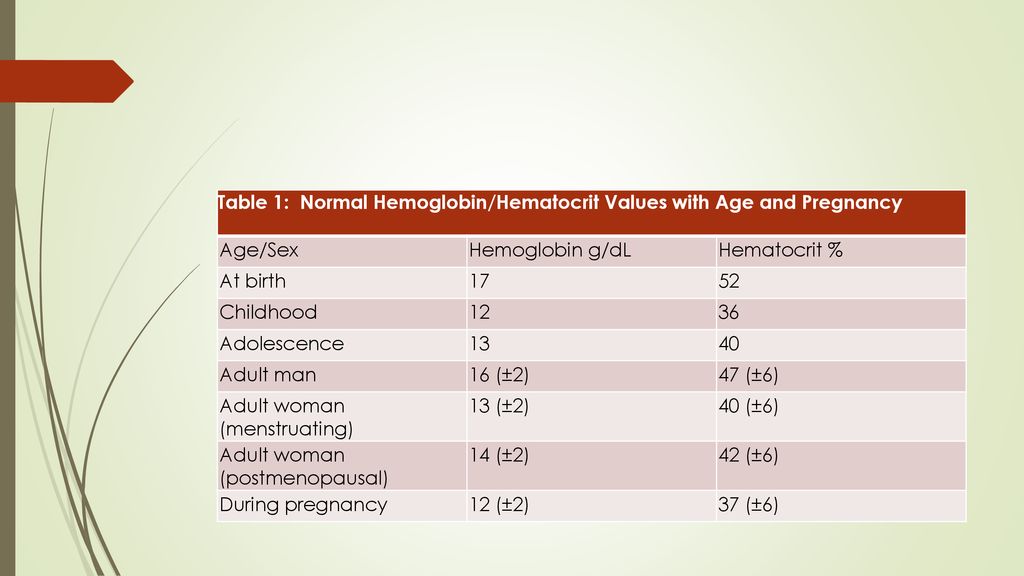

Hemoglobin, anemia, polycythemia, iron deficiency, birth outcomes, preeclampsia, iron supplementation, pregnancy INTRODUCTION Accordingly, higher than normal hemoglobin concentrations should be regarded as an indicator of possible pregnancy complications, not necessarily as a sign of adequate iron nutrition, because iron supplementation does not increase hemoglobin higher than the optimal concentration needed for oxygen delivery. The pathophysiologic mechanism of these conditions during pregnancy can produce higher hemoglobin concentrations because of reduced normal plasma expansion and cause fetal stress because of reduced placental-fetal perfusion. Evidence does not suggest that this association is causal it could be better attributed to hypertensive disorders of pregnancy and to preeclampsia. Epidemiologic studies have also found an association between high maternal hemoglobin concentrations and an increased risk of poor pregnancy outcomes. Very high hemoglobin concentrations cause high blood viscosity, which results in both compromised oxygen delivery to tissues and cerebrovascular complications. High hemoglobin concentrations are often mistaken as adequate iron status however, high hemoglobin is independent of iron status and is often associated with poor health outcomes. Nevertheless, the effectiveness of large-scale supplementation programs needs to be improved operationally and, where multiple micronutrient deficiencies are common, supplementation beyond iron and folate can be considered. Because iron deficiency is a common cause of maternal anemia, iron supplementation is a common practice to reduce the incidence of maternal anemia. Preventing or treating anemia, whether moderate or severe, is desirable. Anemia may not be a direct cause of poor pregnancy outcomes, except in the case of maternal mortality resulting directly from severe anemia due to hypoxia and heart failure.

An association between moderate anemia and poor perinatal outcomes has been found through epidemiologic studies, although available evidence cannot establish this relation as causal.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)